I said goodbye to Dan and Steve and hitchhiked into Mexico today. It feels real- I’m in another country now. An old Spanish church in Ajos.

An old Spanish church in Ajos.

I had my first conversation in Spanish with this guy from Ajos to Why, Arizona.

I had my first conversation in Spanish with this guy from Ajos to Why, Arizona.

I said goodbye to Dan and Steve and hitchhiked into Mexico today. It feels real- I’m in another country now. An old Spanish church in Ajos.

An old Spanish church in Ajos.

I had my first conversation in Spanish with this guy from Ajos to Why, Arizona.

I had my first conversation in Spanish with this guy from Ajos to Why, Arizona.

This kind family invited me into their home for the night.

This kind family invited me into their home for the night.

Lots of Navajo gift shops along the way but beware, they don’t have bathrooms.

Lots of Navajo gift shops along the way but beware, they don’t have bathrooms. After chatting with this Canadian couple at a rest stop for awhile, I joined them on their journey to Flagstaff. Elf (guy on left) used to play what he calls “pepperoni hockey”, just a step below the NHL. His wife said he’s broken near every bone in his body. They travel for four months a year together in their RV chasing sun.

After chatting with this Canadian couple at a rest stop for awhile, I joined them on their journey to Flagstaff. Elf (guy on left) used to play what he calls “pepperoni hockey”, just a step below the NHL. His wife said he’s broken near every bone in his body. They travel for four months a year together in their RV chasing sun.

Camping on the outskirts of Durango was cold last night! A mere 25 degrees made me wake up shivering a few times even with a nice sleeping bag!

Lots of Navajo people hitchhiking from town and back to their tribes. A picture of Ship Rock, one of their sacred sites.

Lots of Navajo people hitchhiking from town and back to their tribes. A picture of Ship Rock, one of their sacred sites. ” I once grabbed a gal hitchhiking in cuba at two in the morning. She told me to let her out in the middle of nowhere and a bartender later claimed she was a wandering ghost.”

” I once grabbed a gal hitchhiking in cuba at two in the morning. She told me to let her out in the middle of nowhere and a bartender later claimed she was a wandering ghost.” “This was my house growing up and it burned to the ground. It was enormous and I can remember exactly how it was.”

“This was my house growing up and it burned to the ground. It was enormous and I can remember exactly how it was.” Hiking at Pyramid Trail @ Red Rock

Hiking at Pyramid Trail @ Red Rock New Mexico sunset!

New Mexico sunset! I finally set off from the Springs today on the firstday of this huge trip. It took a long time and some walking to get a lift near Fort Carson.

I finally set off from the Springs today on the firstday of this huge trip. It took a long time and some walking to get a lift near Fort Carson. “Have you ever seen a hearst with a trailer hitch? You don’t get to take your stuff with you.” – Jimmy the wilderness therapy/ river paddle guy

“Have you ever seen a hearst with a trailer hitch? You don’t get to take your stuff with you.” – Jimmy the wilderness therapy/ river paddle guy

Six rides total so far. Heading southwest tomorrow!

Six rides total so far. Heading southwest tomorrow! On the road, the backpack becomes your home. You want to have all of the essentials ready to go for a good night’s sleep in all conditions. I’m planning to do a good amount of Couchsurfing and staying with locals on this trip, but there will be plenty of times that I need to stealth camp. Stealth camping is the art of making camp at nightfall and leaving at sunrise without anyone seeing you or leaving a trace. Sometimes it’s the safest way to sleep!

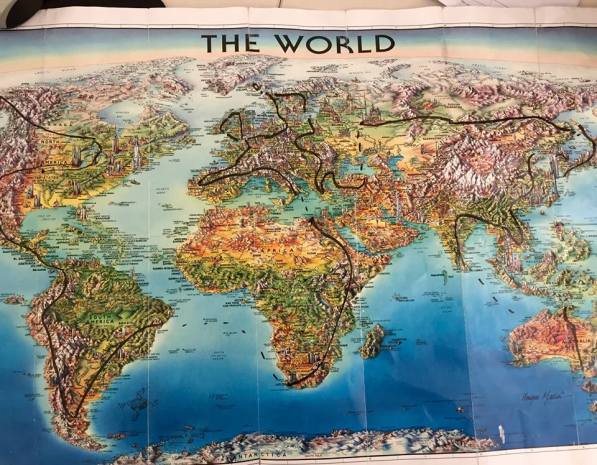

Below you will find my open and adventurous plan to travel the world for the next 2-? years. It’s something I’ve been reading and obsessing and mildly (to most) planning for the last five years or so after doing a few bicycle tours and hitchhiking around Australia, America, and Southeast Asia. Now, finally, comes the approach of the big trip. .

I’ve officially got a departure date. February 5, 2017. I resigned from my jobs and there are a few bit of things I’m having to give up to start this trip. There are the things that I knew I’d give up that are easier and expected: jobs, material possessions, the idea of stability, creature comforts, retirement plans– the things that society constantly pumps us with the message that we are to value. I’ll be trading the illusion of stability for raw adventure. I’m not asking for permission, but asking for some support.

I realize how lucky that I am to be able to do this. There will be dangers, there will be times when I’ll probably feel like this isn’t the right thing to do. I’m willing to face hardships in order to make this succeed. In whatever amount of time it takes, my foolish (to most) plan is to hitchhike and perhaps bicycle in some areas from the United States, through Latin America, through Africa, Europe, Asia, and Australia/ New Zealand. Why do this? The simple answer is that I’ve become completely obsessed. There is a desire to meet people of other cultures without following the traditional tourist patterns. Using Couchsurfing, I’ll stay with local people or camp when I need to.

What will I be carrying? Only the essentials: a backpack with a sleeping bag, bivy sack, small inflatable mattress, 2 pairs of boxers (you can always wash one), 2 pairs of socks (same applies), a journal (to document), a small Martin travel acoustic guitar. I debated over and over again whether I should bring a fold-able bicycle or a guitar and settled on the guitar with the idea that I can always find a low-grade bike somewhere if I want to cycle certain parts of countries. Music is the best way I’ve found to communicate with locals when the language barrier is a brick.

“Life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans.” Indeed, I met a girl who I love (unexpectedly, as it always is) two years ago in a pub in Denver and we’ve had many mountain hiking adventures and experiences together since we met. But she’s for her own reasons not able to join me for this trip understandably, and I have to go it alone. So there are things that you must give up that make leaving very difficult. If I waited any longer to depart, I never would. And this is something I must do because I am determined.

Staying determined through the trip’s natural occurring hardships will be a great challenge at times. I’m hoping that I’m mentally and spiritually prepared for that. A sense of humor always helps.

So if you see a hitchhiker on the side of the road with a guitar anywhere around the world, please pick him up because it might be me! Haha.

Below is an overly generalized version of my intended route. I’ll most likely be flying over the oceans and war zones that I might encounter, but other than that, I intend to remain with my feet on the lands. I want to experience the shift gradual shift of cultures and not just fly into places having skipped over the in-between. Of course, the world is too gigantic to see it all, but I will get a taste (in a very literal way) of all cultures of the world.

The 21st century is beginning as one of the most interesting and trivial times to be alive and I’m hoping to have a front row seat to it all. Through hitchhiking, I can share with all of you the different perspectives and events I find myself a part of around this planet.

This is a particularly long post but most of my daily blogs I intend to keep short due to the fact that I’ll be busy traveling and often be exhausted or have limited wi-fi.

I encourage you all to pursue that which makes you feel the deepest fire and most inspiration. Bon voyage! In early February, I will be hitchhiking south into Mexico and the hinterlands of Latin America.

Leaving Denver in the morning, heading to family for the holidays, I found that my cell phone had fallen out of my pocket on the bus. I backtracked all the way to where the bus and train line meet, where I found the bus driver standing there, my phone in his hand. So I got off to a rough start, yet still, lucky to receive it back.  The first lift came from an Uber driver from tge country of Guinea. I walked and waited a few hours before getting picked up by a plumber heading east. Walking along the highway for an hour or so, a group of three pulled over blasting ICP andother forms of murderous music. One guy was a blabbing drunk, the other girl and guy (a couple) ready to pass out. I drove their vehicle four hours into the middle of Kansas.

The first lift came from an Uber driver from tge country of Guinea. I walked and waited a few hours before getting picked up by a plumber heading east. Walking along the highway for an hour or so, a group of three pulled over blasting ICP andother forms of murderous music. One guy was a blabbing drunk, the other girl and guy (a couple) ready to pass out. I drove their vehicle four hours into the middle of Kansas. It was near Great Bend, Kansas that their drama unfolded and I found myself caught inside the net. They said it was jyst a few miles off the highway for a pit stop but she drove 90 mph along astate road with minimal traffic while her drug dealer boyfriend (he then told me his employment status) caresseda loaded AR-15. I was wishing out of the vehicle but there was no escaping.

It was near Great Bend, Kansas that their drama unfolded and I found myself caught inside the net. They said it was jyst a few miles off the highway for a pit stop but she drove 90 mph along astate road with minimal traffic while her drug dealer boyfriend (he then told me his employment status) caresseda loaded AR-15. I was wishing out of the vehicle but there was no escaping. We arrived in Great Bend alive. The couple ditched the drunk and I found myself stranded, walking in pitch black along a farming road. No idea where I was. No map. It was raining, windy, and cold. Five minutes later, a family grabbed me in their truck after convincing them that I was not crazy.

We arrived in Great Bend alive. The couple ditched the drunk and I found myself stranded, walking in pitch black along a farming road. No idea where I was. No map. It was raining, windy, and cold. Five minutes later, a family grabbed me in their truck after convincing them that I was not crazy. I was mostly miserable. A nice hispanic family invited me into their fiesta and I slept dry in the back of a guy’s truck. I had a conversation with a shirt-off-your-back guy who had lost his job and occasionally thought about jumping off the Lyons water tower. The tower wasdecoratedwith dangling Christmas lights. Out of Lyons, a trucker gave me a lift to Des Moines.

I was mostly miserable. A nice hispanic family invited me into their fiesta and I slept dry in the back of a guy’s truck. I had a conversation with a shirt-off-your-back guy who had lost his job and occasionally thought about jumping off the Lyons water tower. The tower wasdecoratedwith dangling Christmas lights. Out of Lyons, a trucker gave me a lift to Des Moines.

An excerpt from the book “Close Encounters of the Roadside Kind: A Hitchhiking Journey Around America in the 21st Century”:

I hitchhiked through the home of Wayne Gretzky, who has been often called the greatest hockey player ever. You can see why great hockey players would come from this area of Canada, with so many nearby small ponds and lakes that freeze over thick during winter. I was grabbed in traffic by a bloke from England, who migrated to Canada and never looked back. He said, “Years ago, me mate an’ I hitchhiked To France from England with zero dollars in our pockets. Best time of me life. I moved to Canada and like it here. The weather is better.”

One man that picks me up reminisces about his days traveling with his family as a kid. “My father worked in the oil fields in Saudi Arabia, so I was always traveling as a kid. One time I was in Africa and all these guerrilla fighters with machine guns jumped on the bus. I thought for sure, well, this is it, it was all nice, now I’m dead. Well, they grabbed the guy they were looking for and left! It was wild… These days I’m looking to buy a retirement house with my wife in the suburbs.”

My second night in Canada, I arrive in Niagara Falls, a breathtaking blue and white waterfall, a rainbow overhead. Niagara Falls has the highest flow of water in a waterfall anywhere in the world. Loads of tourists from all over flock to the site, snapping photographs, buying overpriced ice cream, tripping over selfie-sticks. Out of good humor, I ask a man struggling with a selfie-stick if he’d like me to snap a photo of himself and his misses. He politely refuses. Really, why carry these worthless products with you? The advertisers have realized how foolish consumers have become, what worthless products they’re willing to by—the selfie-stick proof of this phenomenon. Tourist shops surround the entire area of Niagara. I busk with my guitar and make a few dollars, a few compliments, a few kids dance, until a security guard politely tells me “sorry, you can’t play music here.” The area is excessively touristy at any rate; I’m happy to leave. Along Niagara Falls, just off the railing if one peers over the ledge, you can see heaps of trash that people have discarded over the seasons, never cleaned up: paper cups, cigarette butts, wrappers, faded tourist brochures. Therein is a problem that comes along with global tourism—people’s filth paraded alongside some of the world’s most amazing natural wonders.

I find a small piece of forested area alongside Niagara Falls to camp and fall asleep listening to the gush of the water rushing from Ontario all the way to the New York countryside. Tomorrow, I would follow the water into upstate New York, observe what the river led to.

You can find the full book for Amazon or Amazon Kindle here:

http://www.amazon.com/Backpack-Full-Bush-Dust-Hitch-biking/dp/1511944757

I walk over a river in the morning and chat with a local on the way out of town. My accent is immediately recognizable. ‘Yous’ a yank, are yeh?,” he asks me. He directs me to walk around the bend to where there is a better spot for people to pull over. This turns out to be good advice.

I’m picked up by a guy delivering a BMW SUV and he’s heading north of Bundaberg. We stop in a town to have the vehicle inspected for emissions and safety regulations. I make it to the Gold Coast and ask a couple if they will watch my backpack while I go for a jog along the beach and a dip in the ocean. It is trusting of me but I determine that I have nothing worth stealing inside the backpack anyways.

The Gold Coast is a hot spot for tourists and surfers. The closest comparison I can think of to it in the US would be the beaches in Los Angeles. Therefore, I don’t care for it too much and I hitchhike out of town at nightfall over a red fire sun that is setting over the ocean and creating jaw-dropping images that I burn into my retina. I’m picked up by a local guy coming home from work and driving a meat delivery truck. He is also a country musician of some sort and invites me out to karaoke with some friends of his.

While driving out to the pub, a family of kangaroos are spotted hopping around near the apartment. After a few glasses of whisky, they somehow convince me to get up with them and sing Stevie Ray Vaughn’s “Cold Shot” and it must have been some time shortly after that song that we decide to leave.

May 6

The next day I get a lift from a guy who installs high-tech roofs that are mechanical in that they can open up to let the sun inside. He tells me that he has a daughter that got a basketball scholarship and lives in Austin. Dan sets me off where he has work that morning.

While hitching just outside a McShit’s, I get offered a ride by the first trucky in Australia. He tells me about the speed and Codeine epidemic that was prevalent in the last decade and probably still is in different shapes and forms today. He shows me an extensive log book that his employer requires him to fill out. “It’s tedious, annoying and there are always ways around it,” he tells me.

“There are big fines for not following road laws for truck drivers,” he says. ‘Even for riding in the wrong lane you can get a 600 dollar fine.” That night I make it into Bundaberg and sit down in the bleachers at the local park and watch some people play Aussi hockey. It has nothing to do with ice skates and the “sticks” they players carry are more like golf clubs.

There is a solid cracking sound when a player hits the “puck”, which is more like a baseball. They players wear minimal padding and I’m not sure how there are so few injuries.

I sleep in the park and will hitchhike the two kilometers from the park to the farm I have found work at the next day through gumtree.com, a site similar to Craigslist.

May 8

Wake up at the face of dawn. Start walking towards the area of the town the farmer lives in and a local tells me “I reckon it’s about seven kilometers away”, so it was further than I originally expected. Nobody picks me up. I’m late for work. I start shouting four letter words in frustration.

Minutes later, a farmer pulls up in a silver truck and yells out the window, “You Jack?”

“Yes sir I am.”

“Hop in.”

I was about 20 minutes late on the first day but he turned out to be a considerate and understanding man. He says expressions like “All good” and “righty-o” often.

Later a girl working on the farm admits that she had seen me in the morning but decided that she didn’t like to stop for hitchhikers. I spend the day pulling weeds, toiling in the hot sun and walking through muddy rows of flower plants. I just about ran into giant spider webs while walking the rows a few times.

An Australian cattle dog named Bruiser lounges out at the end of the day as I play my guitar. Hayden says that he will pick me up in town at the park the next morning for work. “No worries, I’ll have coffee ready in the mornin’,’ he says and drops me off for the night.

May 9

Next morning is spent pulling weeds and vines all day at the farm. I’m in need of travel funds so I’m grateful for the work. I help Hayden with a flower set-up in the front of the roadway. Flower business is booming. It’s the day before Mother’s Day.

Later that night, while walking around the town of Bundaberg I run into a man named Allen who invites me into the pub for a beer. I get the impression he is already slightly smockered, but this seems to be his normal state of consciousness. He invites me to come see his boat that he lives on in the water. Flashbacks of the movie Wolf Creek play through my mind. Ultimately, genuine curiosity overrides my false sense of dread.

We paddle out to the vessel on his tinny and he shows me around his small quarters. “I’ve traveled all around the country on this boat, following the construction work,” he says. “This is the life for some of us, as we must. Some people say that I’m lucky to live like this, but there is no luck involved… not like it just fell into my hands.”

I ask him what he thinks happiness is. He ponders this for a moment. “Doing what you said you’d do and seeing it accomplished,” he says. Surrounding us, the lake is calm, spacious. A chill floats in the air and hangs like a timepiece.

Four beers later, he shows me a piece of wood in the center of the boat that moves to the side that he uses as a makeshift bathroom. “Sometimes I push people in there when I don’t like ‘em and turn ‘em to shark bait,” he says, laughs.

Somehow he stumbles his way off the boat and rows me back to shore. Somebody in the neighboring boat shines a spotlight in our faces. Allen holds up a hand to keep the light from blinding him.

“What are you doing?!,” the paranoid person in the other boat asks.

“What’s it look like I’m doing?,” Allen asks.

The man continues to shine the spotlight in his face.

“If you don’t get that light out of my face cunt, I’ll shove this ore up your arse.”

The man keeps the light on us all the way till shore. Some neighbors he has out here on this waterfront.

That night I meet up with Nazarine, the girl that I had met back in Alice Springs. She is staying at a hostel run by Asians and works on a tomato farm. I find out that she has just been leading me on and avoiding me the whole time, she just doesn’t have the courage to say it. I feel like I wasted a lot of efforts and took a detour to come out and see her. She had been the one encouraging me to come see her in the beginning.

I tell her if that’s the way it was, then I’d just assume piss off.

She blows me a half-ass kiss as I walk away.

Oh well. Isn’t that just how it goes sometimes?

May 10

Spend the better half of the day finishing the rows on the farm. Second half was spent around the campfire with everyone laughing and telling stories.

Bruiser the farm dog lazes around the campfire and listened in to our every word. The Ozzies out here are a daring and bold bunch of blokes in their lifestyles and hospitalities.

May 11

The next day I get a lift all the way to Rockhampton by one of the farmer’s friends. They are heading that way to meet up with some friends. We have dinner at KFC and I must head to a park for a place to sleep.

Out of curiosity, I inquire as to what the price of a cheap motel might be in the area. It turns out to be 90 dollars for a night. I walk out of the motel and find a six star motel on some soft green grass in the park for the night.

May 12

A man picks me up near the ocean side in a small town. I’ve been waiting for well over an hour. Hitchhiking is starting to drain me. I need something to revitalize myself.

“I almost passed you up,” he says. “But something in my gut clicked that I should give you a lift. Always listen to your gut mate.”

He tells me that his wife got pregnant a long time ago and he got trapped in the monotony of the working class life. Before that all happened, he used to travel. “I’m well off financially,” he tells me. “But trading up freedom for comforts was not the best decision, honestly although I love my family.”

He drops me off at a grocery store and quickly sticks some notes in my coat pocket, to my protest. “Seriously, please take it,” he says. “I don’t need it.”

Later, I pull out two wadded notes and to my surprise find 100 dollars. I could have got a motel after all last night. Yet that would have been a waste of funds.

I’m picked up by another trucky who nearly skids to the side of the road when he sees me. He sprinkles some pot in his makeshift soda can bowl and has a smoke. He has a definite roughneck edge to him. Wears a straw hat.

‘I got kids with these two cunts,” he says. “Both of ‘em taking all me working money.”

“You should go to Western Australia,” he says. “That’s where I’m from, you probably wouldn’t guess it. The cunts in the city won’t help no one. The blokes in the west are true blue mate.” He sets me off alongside a construction site.

Then I’m picked up by an old man. “I’m on a pension and retired,” he says. “I don’t go to the pubs no more, don’t drink. I just sort of go around these days.” There’s something sad about the man’s tone of voice, like he’s distant, waiting to die.

May 13

Get picked up by a mechanic with two horse dogs who works on the fleets belonging to the local miners.

“They beat the piss out of them,” he says. “They don’t even do maintenance on them; just drive them for thousands of miles till they fall to pieces.

He sets me off and I start walking along country road as the rain sweeps in and I started wondering where I might sleep for the night. This doesn’t look like a light rain; it looks like a potential downpour. I’m not sure how my bevy sack will hold up in that. I need a makeshift shelter. Drainage ditches seem to be the only option along the lonesome country road.

Luckily, an islander with dreadlocks and white guy in the passenger seat pull over and pick me up. They give me a lift all the way to Airlie Beach. I am completely convinced that these guys were angels or some other power disguised as humans. I’ll sleep at a park just before the turn-off to the beach.

“Looks like the weather is better here and glad we could help,” the islander says. “Beats walking the whole way!”

Later that night, the rain faucets down in heavy spurts and I take shelter underneath under the overhang and when that starts to flood I have to take shelter in a bathroom. I don’t get much rest that night. When a security guard kicks me out of the park in the middle of the night I finish my rest across the street at a bus stop shelter.

May 14

A guy driving a Ute is my first ride in the morning to Airlie Beach. Most of the people passing by seem to be tourists so they don’t stop. This guy is a local.

We arrive at Airlie Beach where there is the ocean amongst hostel after hostel. “When the bus dropped me off 15 years ago this was all grass and I slept on the beach,” he tells me. The modernized Airlie Beach has a more tourist-catered feel. Paved sidewalks are everywhere and tourist shops abound. I imagine that it would have been a nicer place to come to fifteen years ago. Maybe I was born too late.

“None of the housing development on the hills was there,” he says, pointing to million dollar mansions overlooking the ocean. “Prices are jacked up here now and so is the cost of living. My partner and I sold our home here and traveled the world for two years.”

I meet a girl named Lynn while swimming near the lagoon in Airlie Beach. She is taking a short break from her life in England to enjoy some of what Australia had to offer. I opt out of the youth hostel (as I don’t like hanging out in areas where everyone else congregates) and I head down the beach and find a secluded spot underneath the trees to sleep. The sound of the receding tide invites me into a state of temporary coma.

May 15

The next day I get stuck in the pouring rain for three hours and countless cars pass me by and nobody picks me up. Grace comes in a small Toyota car with a school teacher from Proserpine inside. He has some good ideas as to what direction the United States should go, he said. “The States should convert to the metric system,” he says. “It would make things a lot easier all around the world. Not to mention all the jobs it would create for the American people in the process of switching over. Just changing out the highway signs would take some workers.”

He tells me that his wife and he have dreams of moving to Spain in the near future.

Then I’m picked up by an Aboriginal guy with a dog in the back seat as I eat my peanut butter sandwiches on the side of the road. It’s not raining anymore. “I’ve lived in Queensland my whole life,” he tells me. He gets work picking fruit whenever he can.

He invites me back to his place for some coffee and we take turns spray painting hitchhiking signs with some leftover orange spray paint he has laying around. We write T-VILLE in bold letters, representing Townsville.

A few hours later I’m picked up by a guy that is a sugar cane train conductor. “In the morning I’m going for a drug test for a new job,” he says, pointing to a container of fake urine in his glove compartment. “It’s no worries, I’ll pass,” he says and smiles.

He also has a passion for motorcycles. “I have lots of biker friends that complain since you can’t ride in groups anymore,” he says. “If you ride in groups of more than 3, you can get up to 15 years in jail. It’s ridiculous.”

Later, a cop shakes his finger at me while hitchhiking. Something tells me the cop has never hitchhiked before. I ignore him and carry on.

I get a lift from a construction worker who informs me about some of the wildlife and especially the ticks in Australia. “I once got one in my head and didn’t know it before I fell asleep that night,” he says. “I woke up with a huge lump on my head.” It sounds like a horror story and I make a note to myself to check over my body for ticks before falling asleep that night.

I check in at the supermarket hotel and they have room in the back where the artificial lights are dimmed out and there’s nothing around but the stars.

May 16

A caravan with a camper trailer cuts us off causing the driver to swerve out of the way. She just about honks the horn but something causes her to refrain. “Oh well,” she says. “Without tourism this town would die.” This is in the small town of Ingham, Australia.

The car rambles on, the motor thumping away at the beat of its’ last legs of life. The lady who has offered me a ride is an older country woman. “We have a chicken at the farm that lays 8 to 10 eggs each day,” she says with a measure of pride.

Hitchhiking has been slow-going and tough in this area.

On a winding road through the tropical region near Cairns and sprawls of sugar cane plantations I wait on the side of the road for over two hours before a ride finally comes. One short ride had gotten me into a tough spot where the traffic was too fast and it was difficult for anyone to pull over, even if they wanted to. I get a lift from an Aboriginal man named Matt, who has picked up a couple that are hitchhiking together all around Australia. Not only are they hitchhiking Australia but they say they have been continuously wandering the roads, landscape and culture of Australia for over five years. They make their travel money from their online business. They seem cautious to tell me exactly what that online business is.

Matt, the driver works for a company called Linked-In that helps Aboriginal people link with their lost relatives from the Stolen Generation. I ask him what his job ensues.

“It’s a mixture of using library databases, computers, and speaking with local communities,” he says. “Some kids were taken away as far as New Zealand, even the United States in some instances.”

Amanda tells me a story about her and Alex driving a desolate road in Australia once and a man came out of the bushes with torn clothing and a three-foot long beard. “We usually pick up every hitchhiker we see, it’s our commitment,” she said. “But that was the one guy we actually passed up. “He looked like he had been living in the bush for years.”

Hours later, we arrive in Cairns and I call Max my host. He says that he won’t be around till tomorrow, so it looks like I’ll be camping again tonight. I throw out my guitar case and busk for awhile and in over an hour I’ve done considerably well. People appreciate the music, except for a disgruntled fat woman who acts as the authoritative manager and tells me I have to move along. I wonder how she would feel if someone came and told her to “move along” with her job? I’m creating a pleasant atmosphere for her customers; some people can be thoughtless and robotic in nature.

I can’t fully blame her though. It’s only the pressures and the weight of the world. Her boss pressures her to behave and remain obedient to the rules of the Corporate Masters.

I stealth camp right in front of the grocery store, in a small island of grass filled with trees. I lay low inside my bevy sack and take shelter from the misty rain that falls and comes down off the mountains.

May 17

Max picks me up the following day and takes me to his mansion at the top of the hills in Cairns. It’s a beautiful tropical spot and his home is surrounded by a rainforest setting. Birds chirp, the wind brings in a breeze that is fresh and pure. I’m greeted by his dog Mango, a spunky red dog that can run like none other and is full of energy.

Max doesn’t let his success get in the way with his passion for helping fellow travelers and making genuine friendships. Being used to sleeping on the streets, these conditions feel like the ultimate luxury to me. It’s a sharp contrast to what I’ve been living like yet it still feels the same.

Max tells me over coffee that he invested in Sydney real estate years back and he lucked out when the market rose drastically in the recent decade.

I borrow his mountain bike and cycle/ push it to the top of a hill. It is 20 kilometers to the top and no easy feat yet the view is incredibly rewarding. I look out at sprawling green canopy and a fresh-lake below. A biologist from Germany stands beside me at the lookout with a set of binoculars. “Look this way,” he says, handing me the binoculars. “There’s an eagle’s nest over there. And you’d never guess what’s over that way, it’s not what you’d expect in this area… there are a couple feral cattle.”

The biologist tells me that the fox bats that live in the area can travel up to 200 kilometers every night. They contribute to the well-being of the ecosystem by spreading the seeds of the fruit they eat in their scat, increasing the trees through the jungle landscape. The new mayor of Cairns has recently made plans to cut down trees that the thousands of bats frequent in the local parks in order to get rid of them and encourage them to live outside of the city.

“The mayor is a fool,” he says. “He sees the bats as a nuisance. Politicians rarely understand nature and how ecosystems work. They shouldn’t be allowed to make these decisions.”

On my way back from the bike ride, I notice thousands of fox bats camped out and hanging upside down in the park, staying cool during the day.

May 18

Max and I venture into the downtown Cairns area and I busked with my guitar for a few hours with slide style and traditional playing. The highlight of the performance was when a few young kids start dancing around and spinning around the telephone pole, laughing and playing.

I meet another traveler named Todd and together we hike to a waterfall. On the way in, we run into a baby brown snake that hisses and lunges at us, fangs bearing. I nearly walk on top of it since it blends in with the twigs and sticks along the trail. I jump back quicker than I think I ever have before!

Swimming underneath the waterfall is a feeling like none other. There are few tourists in the spot too which makes it even better. It is cold and refreshing. Max and his partner Jacob cook a great meal and in the morning, they will set me off on the road that continues back south to Townsville and then I will head west back to Katherine. I am going to try another attempt at making it to Western Australia.

May 19

The next day they drop me off along the road and I’m heading southbound back the direction I came from. It takes at least three hours to get a lift and I just throw my backpack down on the ground in frustration. I have a seat and listen to the wind blow in the trees. Somehow, it speaks.

I’m given a lift by a wild trucky who nearly slams on the brakes when he sees me and pulls right over. The patience has paid off. “Oh so you’re an AmeerrrrrrrrriCAN!,” he says frenetically as we drive off into the setting sun. He tells me that he doesn’t take his job too seriously since it’s just extra income to support his family.

“I blow glass and sell it on the black market,” he says. “I make more than twice the money doing that than what I make in the trucking business. My father got me started with blowing. He gave me a four-year internship.” His rig is two trailers long and he’s got just a few stops left for the day. He’s come all the way from Sydney at the beginning of the day.

We stop at a meat shop and deliver I help him unload some of the day’s meat.

He blasts his speakers and puts in music from Aussi rock bands from the eighties and stereotypical trucky music. There’s something great about this since Jim isn’t your typical trucky; he’s somebody with dreams. He runs over a dead kangaroo on purpose just to mess with me. I brace myself for a giant bounce in the cab but the beastly rig doesn’t even tremble in the slightest.

What I really remember about riding with Jim is that we were laughing hysterically the whole way to Townsville. “This is a lazy man’s job mate,” Jim tells me and pops a DVD in the DVD player. We watch cheesy American war films from the seventies and eighties. He even invites me to stay at his hotel and we have a steak meal. Tomorrow I’ll be doing the same thing I’ve been doing—that is, leaving town.

May 20

I leave the hotel about eight o’clock, an hour after Jim has already hit the road. Before he walks out he wishes me luck, coffee cup in hand. “I’m an Australllliiiiian!,” he says, and walks out the door with a laugh. As I wait out at the best choice hitchhiking spot I notice lots of prison guards on their way to work. Obviously, there is a prison somewhere in the area and this factor doesn’t make for good hitchhiking.

Eventually, an older guy pulls over on his way to Richmond and wants the company. He is a veteran with World War 2 stories. He tells me how the English had sent in the Aussis to the front lines but when the Japanese wanted to invade Australia, only the Americans had come to aid.

“I had a friend who fought in Vietnam and had to hide in a ditch in the jungle by himself. The adversary was onto him and while he was hiding, the Vietnamese pissed on him from on top of the hill. He didn’t want to blow his cover, so the poor bloke just had to take getting pissed on.”

The man is full of stories. One of the best ones, however, is a story about a joy ride he took with his hot rod as a young bloke. “I was out for a joy ride and nearly ran over a cop who jumped back while I was passing a car. The cop jumped in his cruiser and followed but I cut off to a side street and got away and he never caught up with me. Anyways, twenty years later I went to a party and the guy that used to be a cop comes up to me and says,’ you’re the guy that nearly ran me over 20 years ago! We were searching for you!’ Anyways, we both had a good laugh over that one.”

I ask him what life is like out in this part of the country for most people. “Well,” he says. “People out here might come across hard at first, and maybe they are—but they’re darn hard workers mate. It takes a certain kind of perseverance to get by in this kind of country.”

He has some borderline racist views towards the Aboriginals. “They were only here 200 years before the Europeans came to the continent at most,” he says. “Half of their cave dwelling artwork was made recently with white man’s paint, so they just use it to claim it as sacred land. Most of the times, they’re just trouble. They have been known to hunt the farmer’s local sheep and drag them into the forest. Also, they have been known to poison their babies in some instances… I have a friend who’s a nurse that has told me stories. ”

I just nod my head and listen. I suppose everyone has an opinion.

At the gas station where he drops me off two Germans are camping in their van with a cardboard sign that has been written on with a black marker. STRANDED: NEED A TOW, it says. I say hello and ask them how long they’d been there. “Three days,” the girl says slowly and clearly, with a trace of resentment and trepidation in her voice.

I buy them a bag of chips and a couple sodas and wish them luck. I imagine it’s hard to find a cheap mechanic in this desolate area considering that they probably live miles away and are the only mechanic shop in the area. Probably some kind of monopoly results with spiked prices.

I wait for an hour for the next lift. The landscape is dry and barren and the wind picks up the speed. I’m truly in the middle of nowhere, where only a lonely gas station and cattle surround me. It’s like Texas in Australia here.

I take out my map and have a look and it sinks in just how huge the expanses are between towns in this part of the country. Often, there is nothing for miles and miles. Then it dawns on me that I’m sitting on the wrong side of the road (the American right side) and it’s no wonder that I’m not getting any lifts! The sun must be getting to my head.

Hawks circle the road, searching for carcass to scavenge. Leaves blow in from the wind and there is the pungent smell of cow shit. The sky is baby blue with only a few faints wisps of white clouds.

I luck out and two girls pick me up on the way to the mines, one of them particularly cute. “We work near the mines in Cloncery,” they tell me. The girl shows me a picture of her operating a piece of machinery. “I get to work in an air-conditioned truck all day so it’s not so bad,” she says.

The girl in the passenger seat tells me that she had a friend in jail who met Ivan Milat. “He was a scary guy,” she says. “He sat all by himself in the cafeteria and he used to have menacing jokes with the other inmates. He used to say ‘what’s the difference between a German and a French backpacker? Ten meters, he would say.”

I set up my guitar once we are in town outside the grocery store as my food funds are running low. A group of Aboriginal kids run up to me and start firing a million questions. “Did you walk? Where’d you come from mate?! How long will you stay here? Why are you traveling?”

It’s a bit overwhelming but the kids are awesome and full of energy so I buy them popsicles once I make a few dollars. A guy pulls over and hands me his number on a piece of paper, tells me that he can offer a place to stay for the night if I’m interested. A miner limps into the supermarket and is missing an arm. I can only assume this is the result of a mining accident. Some people have rough but they remain resilient for their families.

Everybody knows everybody here but the locals are accepting and trusting. They allow me to play in front of the supermarket with no problems.

That night, the Aboriginal kids help me find the guys’ house who had offered a place to stay. We walk through the streets in the darkness of night, some of them on their bicycles. One young kid not older than 14 lights up a cigarette and takes a drag. “You shouldn’t do that,” I tell him. “It’s really bad for you.”

He smiles. “We die young though,” he tells me simply. Maybe he’s right. He recites the lyrics to a 2Pac song. America’s influence on every street corner; maybe it’s a dirty shame.

Every night, the kids say, they play a game of “run from the coppas.” There is a curfew for the kids at 9:30, which they dutifully do not follow and make a game of the whole thing. This is the fun they have living in this small town.

I can’t help but quickly grow attached to these kids. They don’t have much and neither do I. I feel like these kids’ chaperone on a retreat. At the same time, they’re giving me a tour of the town through their innocent eyes. “That’s our school,” one kid says, pointing to a tiny building with faded white shingles.

A quiet kid who follows close to my side speaks up. “My dad’s dead,” he says out of the blue. “I found my Dad hanging from a rope in his room one day. I miss him.” The crickets stop chirping, the world stops spinning and I can’t think of anything to say. I hand him a guitar pick, pat him on the shoulder.

We finally arrive at the guys’ house, only to find out that from a tentative woman that answers the door who says “he might have been on drugs tonight and there is no place for you to stay.”

We depart and I begin the search of finding a soft piece of green grass in this late night hour.

I camp next to a church and am haunted by mosquitoes and the occasional familiar ghosts.

May 21

Nothing but the crows leaving this town

In the morning breeze, locals must know better

Home is where you’ll never leave

I write in my journal in the morning as I wait for a ride. As I’m sitting on the concrete steps next to the local library drinking my morning coffee, a dog comes zipping frenetically out of nowhere and rolls over, has ten seconds of bliss, and runs off again. Happy as a free-roaming dog in a small town, since that’s what he is. His name must be Freedom.

I try some delicious pastries from the only bakery that sits on the corner, recommended to me by a couple road workers. “It’s the only place to go,” one of the guys tells me.

Eventually the dust clears and a guy that works in the mines picks me up. “I heard you playing your guitar in front of the store last night,” he tells me. “I dug your music and when I saw you standing there I was like ‘whoah, that’s the same guy!”

He offers insight on the mines surrounding Mt. Isa. “In Mt. Isa, the industry is worth 2.3 billion dollars a week, after wages and taxes.” If the mining in the areas were to end or come to a halt, many of these families and residents would have to simply pack up and leave. There would be nothing left to sustain them.

He tells me a heavy story about his friend who was bitten by a brown snake, which has deadly poisonous venom. (What snakes in Australia don’t carry deadly poisonous venom?)

“We were out four-wheeling and he happened to be in the wrong place, wrong time,” he says. “He’s stepped off his ATV and the snake must have been underneath him. He stepped off and the snake was right there. He walks up to me, almost casual-like, trying to keep his blood from circulating too fast and says ‘mate, that snake, it just bit me’. So I got him inside my Ute and I floored it all the way to the hospital, nearly ran over an old lady at the front entrance. They had to amputate his leg. There was nothing else they could do and he was lucky he didn’t die that day and could take his life home with him.”

The hard red and dusty landscape passes us by. “People have your back in this part of the country,” he says. “We depend on each other. You have to live that way to survive. To this day, my mate still says ‘if it weren’t for you, I wouldn’t be here’. I just tell him that he wouldn’t have been bitten if I hadn’t suggested going four-wheeling together!”

Jake is a down-to-earth kind of bloke. Most people that offer rides while hitchhiking tend to lean that way. Halfway into the ride, he tells me that his father is a billionaire investor and recently purchased a 400,000 dollar house for his partner and him to share. In either fate or coincidence, it turned out that the house actually belonged to his girlfriend’s grandfather at one point in it’s’ history.

“My Dad always takes care of me, but I wish I could see him more,” he says. “He’s always busy chasing the next investment, the next big deal closure. I called him the other day and he immediately asked ‘do you need money?’ and I was like no…”

“I wanted to tell him that I just want to spend time with him but I just couldn’t say it,” he says.

Once, his Dad took him around in a rented Lamborghini. “Once the speed reaches above 150 miles per hour, the back side actually raises up and is grounded in the front,” he says. “It was the biggest rush of adrenaline I had ever experienced!”

Jake’s heritage comes from New Zealand and his father originally came from being dirt poor and having nothing. “His x wife tried to bleed him of everything he worked for,” he tells me.

I tell him about the drug-addict that had offered me a place to stay last night but had been out of his mind.

“Mt. Isa also has a lot of drug problems,” he confirms. “Mt. Isa is also a helluva a place to get stuck mate.”

Two hours later, I’m stuck in Mt. Isa and frustration of the passing cars returns. The mechanics at the local shop watch me from across the street. The mining infrastructure is massive amounts of machinery and giant metallic buildings that blow out smoke and pollution beyond your wildest dreams. Further than your farthest nightmares.

I kick at clumps of dust and rocks. Even reading my current book or playing my guitar doesn’t’ sound enticing. I swat the hundreds of flies away from my face that try desperately to dive into my eyeballs. I desperately try to swat them with my shirt—the disgusting maggots are quicker witted than I.

Hours later, just before the giant red ball of fire slides behind the floating chunk of Earth, a white van comes screeching to a stop. The door slides open. A cloud of dust explodes into a mushroom cloud.

Inside the van, there is a bed and four French people squeezed into the back along with their backpacks. “Hop in!”

It’s like God has sent this dirty, stinking van to my rescue in this God awful dirty, stinking town that smells like coal. I throw my dusty backpack inside and hop in knowing full well that as always, I’m in for a ride.

May 22

An insect blends in with the tree and its’ surroundings so that it can survive, so that it won’t be eaten by the bigger creatures and swallowed up by the bigger things that surround it. In some ways, people are the same way. People blend in and conform to social norms so that they can feel comfortable, safe, so that the system doesn’t eat them up. Maybe this is the reason that franchises and corporations are starting to decorate the world landscape.

Are people by nature scared to try new things? It is easier to always experience the monotonous?

We’re all just pawns, destined to be moved by someone else if we don’t move ourselves.

These are the kind of philosophical conversations we have in the back of the van. We just lounge out in the back as the miles pass by in the night. The back of the van smells like yesteryears’ dirty socks and wet dog. None of us mind this and the French guys that picked me up simply don’t give a shit. That is their freedom, their philosophy to live by, moment to moment.

Their tactics for acquiring road funds involve setting up a cardboard sign in front of gas stations and busking for gas money. Their sign reads: SOS- OUT OF GAS! They tell me that originally their sign actually said SOS-NO GAS! but somebody called it in to the local police thinking that they were Green Peace protesters against the shipment and consumption of petroleum. So they reinterpreted their cardboard sign.

At one lonely gas station, we have just started jamming and an old Aboriginal woman steps out of the car and hands our driver a 100 dollar bill. It is shocking to me. When the French guys start packing up their guitar I’m a bit saddened that the jam has ended before it even began—it was just getting started. They explain to me that it’s respectful to leave after some has offered to fill your tank so they don’t assume that they are using the money for something else.

These desert towns are strange places and take on a life of their own. Everyone is either transitory or stuck with no in between. One Aboriginal man that seems to be in the stuck category offers our driver sixty dollars at one spot in exchange for buying him a case of beer. The town has limits on how much beer one person can buy per day—not that any rule ever kept people from getting their fix.

Our driver consents to this and the man comes over and siphons the gas out of a can using his mouth. “Don’t you want something to wash out your mouth with?,” the driver asks, offering some water.

“No, it’s alright mate,” he says. Siphoning gasoline seems to be an accustomed practice for him.

Night falls and we stop at pub that has old bicycles set up in the front for decoration and a few locals zombie around inside. I walk inside later after taking a short walk around the park by myself. The two French guys seem to be in some kind of argument with the bartender. He has sold them beer and then tells them they have to drink it away from the pub, even though there are plenty of open seats.

“Yes, but I gave you the take-away price,” he tells them.

“The price wasn’t cheap,” the French guy says. “I don’t think you offered us a special price. Why can’t we just drink these out on the patio?”

The bartender won’t have it and he doesn’t take kind to travelers. However, he takes kindly to the funds that travelers bring into his establishment.

“Then why do the others get to drink inside the bar?,” the French guy persists.

“Because they paid more for the beer. You do the math.”

I try to make eye contact at let them know that it’s best we leave even though this guy is a complete dickhead. We defiantly pull out a table from the back of the van and set it up across the street. We play cards and drink beer on the other side of the bar.

A massive tourist bus pulls up alongside the pub. Its seats are empty with the exception of the driver. The driver walks in and comes out after a few minutes with two cases of beer.

We theorize that the driver must have a contract with the pub to bring tourists into the pub every day. In exchange, the pub owner offers him heavily discounted or absolutely free beer.

I remember what the pub owner had condescendingly said. You do the math.

That’s what tourism business becomes when it mixes with giant industry—impersonal and only a matter of numbers. The relationship becomes one of capital and loses all personal human touch. The traveler is seen as a walking bank to some greedy establishments.

I’m not bashing Australian pubs here—most of the pubs I walk into are full of people full of life and open to more conversation and life outside of pocket books. This is an element of the tourist industry that is prevalent in some areas, however, some more than others.

We stay up till the early hours of the morning chatting, laughing and playing cards. Sometimes they will go into French-mode and I can only get the gist of what they are saying.

Defiantly, the French guys park their van across the street in front of the pub and go to sleep. In the morning, an old lady walking her dog whines about us sleeping along the roadside and commands us to pay and “sleep at the RV Park next time.”

In the middle of the desert, we climb to the top of an old wind mill. Around us, blue sky and golden desert, a vast openness and isolated independence.

May 23

We arrive in Katherine and I find myself in the small Northern Territory town for the second time. I’ve officially hitchhiked around half of Australia; what remains is Western Australia, the large expanse of the west. The town seems just the same as it was just over a month ago. The Aboriginals hang out in the shade of trees in the parks. Locals and tourists hang out near the hot springs. Time hangs on like a clump of bush dust.

I go for a hike along the trail near the springs. Abandoned rusty automobiles and white gum trees decorate the yellowed dry landscape.

Shelby, my Couchsurfing host, meets me in the park as we play cards. I grab my guitar and backpack full of Australian dust, say goodbye to the French crew and hop in her car. I find myself in the company of a few local teachers for the night and we go out to the pub for drinks and dinner. She tells me that there is a high turnover rate at the schools in Katherine and not many teachers stick around long-term. Shelby is one of the few that does.

She tells me that she is going to a music event with her friends the next day and to my luck they are heading to Kununurra, which is a small town the northwestern Kimberly region of Australia. This is reassuring, as it means that I won’t have to get stuck waiting for a ride out of Katherine for three days as it happened last time.

May 24

We cross into Western Australia and the landscape changes drastically. Steep rocky escarpments cut through the dry land and Boab trees pop up through the soil. Boab trees are iconic to the landscape of Western Australia, some of them living up to 1,500 years old. They were used as food, medicine, and shelter by the Aboriginal people and when the white settlers came, they were used as directional markers as well as makeshift prison trees in some instances. The Boab trees seem to reach up to the sky in a fifty-finger claw; they are some of the oldest trees in the world and each tree seems to take on a distinct personality of its own. The only other place in the world you can find Boab trees is Africa. Some theorize that early nomadic people brought the seeds from Africa over to Australia but the most likely theory seems to be that Australia and Africa were at one point in distant history a part of the same land mass.

We cross the Western Australia border and the billboard reads : Western Australia, A Great Place. It was like the planners couldn’t think of a better way to advertise this part of the country. You can imagine them sitting at a table, dressed sharply in business suits. “Well, any other ideas for slogans, anybody?”

“Hmmm… how about ‘Western Australia: A good place.’

“No Frank, that one’s been used before. We need something snappy, something attention-getting that will really reel the tourists in.”

Someone raises their hand.

“Oh, I know! Western Australia: A Great Place.”

“ Ok, good enough. Let’s go with that.”

I spend a good portion of the day playing guitar with my case open in front of the local Woolworth’s with a cardboard sign that reads: Looking for a lift to Broome. A German guy introduces himself as Wolf and says that he’s heading to Broome in the next couple days and is looking for a travel companion.

“I just have to wait till I can get my truck fixed,” he says. He jots down his number on a piece of paper and tells me to call him in a few days.

Later, a fat woman in a security uniform approaches me. “ Did you know what you are doing is illegal?,” she asks condescendingly.

“Illegal?,” I ask her. I wasn’t aware that playing music was illegal in this part of Australia.

She leans over and her voice turns to a slight whisper, as if to let me in on a secret. “We have a big problem with the Aboriginals,” she says. She says this as if she were talking about the local mosquito problem.

Aboriginal people are hanging around, some bored, some talking to each other. In all fairness, earlier there was a fight between to Aboriginals that lived on the streets right next to where I play. When they hear me playing, they suddenly stop in the middle of the fight and listen to the music, seemingly forgetting about what they were doing before.

“I don’t see a problem with them,” I tell her. “I’m just playing music.”

She won’t have it. “Rules are rules,” she says. It’s not my country and it’s not my town. I pack my stuff up and walk on. Small minds often speak the loudest. Why is that?

As I’m leaving an Aboriginal guy in a blue and white mechanic’s uniform walks up to me, extends his hand. We shake hands. His eyes are blood shot and his words are slurred.

“The name’s Crow,” he says, pointing to his red name tag. The name tag reads Crow.

I ask him about the concert and how much it costs to get in. “Yes, there is a concert mate,” he says. “But people like us, we don’t pay. We don’t go through the front gate… we go around.” He speaks in secrets, whispers, an ancient demeanor.

While walking towards the concert I run into an old eccentric German man. “I’ve lived in Australia for over 30 years,” he tells me. “But I can remember, I was 8 or 9 when Hitler paraded through the streets of my home town. I can remember when my sister died when mortar came crashing down when the Americans bombed our house. I was in the other room and I’m lucky even to be alive.”

We start walking and find ourselves passing a fancy pub. Being a true German, he says, “Let’s go get a beer, fuck it.” We walk into the pub and an Indian man who happens to be the owner looks at my jug of orange juice that I am carrying along with my backpack and says, “you can’t drink that in here.”

Old Man Markus glares at him. “Of course we didn’t come here to drink orange juice, we came here for a beer,” he tells the owner bluntly. “What the fawk did you think we came here for?” The small Indian man walks off.

We have a seat at a table on the balcony. “See, all these people wasting their time,” he tells me. “Like that Indian man that owns this place. Why doesn’t he just mind his own fuckin’ business, ya know? I don’t have time to waste. I could die any minute. I know it’s not a good way to put it, but it’s true. “

He then goes on to tell me that he recently found from his doctor that his aorta has doubled in size and is on borrowed time. “The doctor told me that I should have died months ago,” he says. We catch a bus to the music festival and are let down by the mediocre music acts that are performing.

“It’s gotten worse every year,” Markus says. “I’ve lived here for five years and it’s like the more they promote it, the more they charge, the more hype there is, the worse the bands get. I told you, the concert is not worth even sneaking into for free, let alone paying for it.”

Markus shows me a “good spot” in the park that I could potentially camp for the night. I notice that there are sprinkler heads in the area. “Won’t the sprinklers turn on?,” I ask him.

“Oh no, you don’t have to worry about that,” he says. “I live across the street and I’ve never seen them turn on during the weekends. Besides, if you stay in this gazebo, the sprinklers wouldn’t even reach if they did turn on…”

Markus takes off for the night and that night, not only do the sprinklers turn on but they come blasting on without warning and I have to make a mad dash with all my stuff across the park. Not without first getting blasted and completely soaked. It’s one in the morning.

May 26

At first, I wake to the sound of birds and the crack of a sore back. I’m still wet from the night before. Then I feel a sharp pain in my shin and realize that during the night when I had to move I had coincidentally laid on a fire ant colony! I jump up and do a wild dance and frantically brush the aggressive ants off my body. Who needs coffee when you have fire ants?

I grab a shower from the local caravan park and start walking out of town. The first lift comes from a guy driving a taxi van, offering lifts to people to the airport. “I was heading that way anyways, so I thought I might as well offer you a ride,” he says. He is picking up a woman from the airport to drive her into town.

Just two kilometers on the outskirts of town the trees disappear and open up to a wonderful canopy of sun-blistering hell. Not even the birds venture here; there is not a single tree to perch upon. I take my shirt off and use it to cover my face. An hour later, no cars have stopped and I walk another few kilometers till I find a sole tree in the middle of the dry landscape. I throw my backpack to the ground and dust blows everywhere. I use it as a makeshift bench and read my book, jumping out every time I hear the sound of rubber on pavement speeding by.

Still, nobody stops. Two hours later.

I’m starting to think of heading back into town for now but a silver car comes scooting on by and without even bothering to get up from the tree, I shoot out a half-ass thumb. My request is acknowledged and the car pulls over to the curb.

Joe and Kelsie are heading to El Questro to camp and experience the water gorges and waterfalls the area has to offer. That’s the great thing about going into a trip unplanned; you don’t know what’s around the corner and everything that you are in for is a surprise. Not always a pleasant surprise but more times than not, it is.

Joe pops in a CD and we listen to the Avett Brothers as the road winds along. At one point, we witness a wild dingo walk into the road and then dart back into the bush.

The cities have the tendency to bore me but being out in the wild is a ceaseless opportunity for amazement. Joe and Kelsie are young and in good physical shape so we go for a jog through the rocky trail that splits through the creek and make our way to Emma Gorge. Water cascades off a 500 foot cliff edge and the water is the perfect temperature—icy fresh cold but not freezing cold. After jogging through the heat it feels like paradise.

I hike to the top of a hill at sunset by myself while Joe and Kelsie tend to their camping spot. There is live folk music around a campfire and we grab beers and share some laughs together. We meet another guy who is traveling around Australia on a BMW motorcycle. Tomorrow morning, we will hike more gorges together and then I’ll head back to Kununurra.

May 27

After a day spent hiking and experiencing some of the wild gorges, I set out my guitar and busk in front of a gas station. While busking, Wolf stops and offers an Emu Export beer. He says that he’s going to leave tomorrow no matter what along the Gibb River Road and he’d like the company.

I sleep on the outskirts of town one last time and in the middle of the night a kangaroo comes rustling around my campsite. I sit up in my sleeping bag and the kangaroo stands there stark for a moment, stomps on the ground and then darts off into the warm night. It’s a moment that is fleeting, memorable, and tingles my nerves with a spike of adrenaline.

May 28

Wolf and I just nearly miss each other the next day. Sitting bored along the side of the road, I decide to go for a short jog, leaving my backpack resting on the trunk of a lonely gum tree. As my luck would have it, it is just that moment that he comes driving by looking for me and drives off when he doesn’t see me. I notice him from the other side of the trail and try running up to him, shouting out, but to no avail. Coincidentally, there is a jogger moving alongside the trail at that exact moment that I am able to flag down in order to borrow her phone and call Wolf. Wolf turns around and picks me up and we are off.

It is the start of one of the best adventures of the entire trip. The Gibb River Road stretches from the outskirts of Wyndham to Derby. The road stretches for about 660 kilometers of desert through the Kimberly region. During the wet season (November through March) the road often experiences mild to severe cases of flooding. In recent times, many sections of the road have been paved but other sections still remain single-track dirt road. The road does not take kindly to vehicles that do not have four-wheel drive capacity.

We take to setting canned beans inside the engine bay of the four-wheel drive truck. This way, we don’t have to stop to start the propane burner and we could use the engine’s heat to warm our lunch. The landscape is hard dirt and clay-looking mountains.

For the next two days, we make sure to stop at every gorge that we possibly can. We swim at every spot and often miss the loads of tourists that come by on gigantic buses. One time, we just made it out of a gorge just as the bus rolled in. “They’re a danger to the environment,” an Aussi guy jokes on our hike out.

We stop at a gorge and I take the best shower I have ever taken underneath a rocky surface where the waterfall falls onto me. Huge spiders drape their intricate webs around the water hole and I observe small dragonflies darting in and out of the air eating even smaller bugs.

The Aboriginals had told me that there was a certain ant that you could eat that tasted sweet. You would have to eat the backside and the ones to look out for were the green ones. Finding a green ant, I try eating the backside. “Well?,” Wolf asks.

It tastes like ant guts without a hint of sweet. “It’s disgusting,” I tell him. “Definitely not the one.” We get a laugh out of this. Ropes have been tied to the branches of some of the trees and we climb to the top and jump into the water like wild Neanderthals.

Every night I unroll my sleeping bag and sleep on top of the truck under the stars. Wolf and I drive the truck through the sand along a beach area and make camp in a solitary area away from the other tourists. Dry wood is easily accessible and scattered around the area. We build a fire with flames that reach upwards of ten feet into the air, the licks of flames of which reach to the heavens. We tell stories and jam on our guitars for a few hours and in the morning hundreds of cockatoos come to the area and wake us up. One of the songs on our repertoire is of course Wish You Were Here by Pink Floyd and I take to playing some slide guitar lead while Wolf strums and sings the rhythm part. It’s the orchestrated sound of a jungle circus.

On one trail, we nearly run over a black glossy snake that appears aggressive; squirming about and making every futile attempt to bite at the giant piece of metal that hovers over it. I’m no snake expert but I’m certain the snake would absolutely be classified as deadly poisonous.

Since we are running low on gas we hitchhike the 13 kilometers into one of the gorges and are picked up by a man who is on vacation by himself. “My sister and I came out to this gorge at night time once and we saw the red eyes of many crocodiles,” he tells me. We both have a strong desire to see this during the day.

The hike is easy and mostly flat along the gorge’s sandy bank. Dozens of fresh-water crocodiles rest in the water and along the sand. At first glance, many of them appear to just be logs floating along but at closer glance you can see that they are prehistoric survived reptiles. It’s one of the most amazing atmospheres I’ve ever experienced. We try to venture as close as we can get without feeling like we are in the croc’s territory to get pictures. These are fresh water crocodiles and not as dangerous as salt-water crocs. Still, there have been instances when fresh water crocodiles have attacked humans.

On the way back, we’re offered a lift from a car full of ladies. The mother is old enough to be a grandmother and sits in the back with us. Just to have fun, I have dressed up wearing one of Wolf’s ties that he had in his car and the ladies get a laugh out of this. “You look ridiculous!,” she says and tells us to get in. “But please,” she says in proper English humor, “Do take that tie off!”

“Here’s the rubbish bin… should we drop you off there?,” she jokes with us. She chides her daughter, who is driving to stop hitting the ruts in the road. “Drive on the other side!,” she tells her. “You’re giving us a headache back here!”

I take a dip in the cold water of the river back at camp but not for long, the thoughts of green reptiles with rows of jagged teeth that could potentially bite me in half still fresh in my mind.

May 30

We drive into Derby and Wolf decides that he wants to find some salvaged part for his Toyota 4-runner. After asking the locals we somehow find our way to the “salvage yard” with in actuality turns out to be an Aboriginal community. Asking around for directions to the salvage yard, we get confused looks and various offers to sell their vehicles.

Neglected houses in various stages of decay and a seemingly abandoned basketball court. Broken doors, sagging porches, dirt roads, rudimentary shelters made of tin and wooden poles. An Aboriginal woman approaches us, alongside her three young kids and a scraggly-looking dog. Her eyes are a bloodshot red and she has a beer in her hand. Sadly, this almost seems like a cliché.

“You have Ganja?,” she asks and sways from side to side. We tell her that we didn’t come looking for Ganja nor do we have it.

We thank her for her time and we drive around the community. One house has a Toyota 4-runner in the driveway and seems like it hasn’t been driven in years. Wolf pulls into the driveway. Four kids gawk at us, one of them wearing an AC/DC shirt.

A woman comes out onto the lawn and he explains that he is looking for a Toyota truck to take parts off of. “How much you give me for car?,” she says.

“Well, I didn’t want the whole car, just some parts, but it has to be a manual transmission… is it a manual?”

“Ok, this one automatic.”

She tries to sell us her other car but it is not what Wolf is looking for. Seeing that there is no sale to be made, she asks for a ride into town. We would have happily given her a lift to town had the truck not been loaded to the brim. In hindsight, I could have strapped myself to the roof if I had felt up to it.

This experience leaves me feeling slightly sad at their condition although there does seem to be a strong sense of community, tainted heavily by drugs and alcohol in this particular area. It’s the all-too-familiar infliction of white man’s medicine in a place it shouldn’t be.

That night, we find a place to camp alongside the beach in Broome. Gathering firewood along the beach before dark, we make ourselves a steady, slow-burning fire. We meet an old Australian who has been traveling the country long-term. He joins us at our fire with his dog Blue. A small crab comes in off the ocean and crawls near the fire for heat. I pull out the guitar and find myself playing guitar.

“You can play that guitar Yankee,” he says. His dog Blue is anxious and seems like he wants to go explore. “Blue sit down boy, you can’t go to the beach, there’s a four meter croc down there!”

He informs us that a giant crocodile has been spotted in the area recently. Without a doubt, I’ll be sleeping on top of the truck for the night.

May 31

The sound of ocean waves washing against the shoreline was a comforting alarm in the dawn’s hour. Wolf is already down at the ocean playing guitar, trying to work out the chords for Zeppelin’s Rain Song.

Tom, the man we had met the night before, invited us over for coffee at his site. “I used to own a home along the coast of Sydney,” he says, pouring us both a cup. “I wasn’t happy though, everyone leeching off you, I was lonely. I live better just camping like with no bills.”

A few minutes later we walk back to our campsite where Wolf had left his guitar alongside the shore. To his shock, it is now floating and submerged in the ocean. He runs over to it and we quickly try to dry it off and set it on top of the truck to dry. The guitar will definitely be damaged but perhaps we can prevent it from damaging further.

Lesson learned: never underestimate the tide and the tide is always changing, often faster than you might think.

June 1

Wolf and I make camp along Cable Beach in Broome, which despite the hype by other travelers, turns out to be a touristy spot. It is a place that has changed much in the last ten years, the locals tell us. Tourists ride an ocean path on the backs of camels in the setting sun.

Wolf and I depart and I find myself walking again, hitchhiking in a southern direction. In a matter of minutes, I’m picked up by an Aboriginal guy who is a primary school teacher. Five minutes into the ride he seems to be slightly irritated, maybe tired and then I realize that last night was rough and he’s sharply hungover.

“I’m hung over from the horse races last night mate,” he says. I end up driving the 150 kilometers back to his community for him and he falls asleep in the passenger’s seat. He hands me a banana and jots his name down on a slip of paper. “If you get stuck, just call me,” he says. “Might be able to put you up tonight if it’s ok with the wife.”

The desert is dry and hot and there is one car that passes by for every five minutes. The next lift comes from a French guy named Vince. He is heading to Port Hedland the next day, so I decide to camp at Shell Beach with him for the night. Instead of paying for the camp, I just hike out to the Oceanside and sleep by myself in my sleeping bag. The sound and caress of the sea breeze puts me to sleep. It sure beats camping next to the noise of a bunch of other travelers and paying for it.

The sun is a red-rimmed fireball setting over the deep blue ocean, deeper than anyone can possibly fathom. The colors change to reflections of purple, orange, yellow as it sets; the last remnants of light shimmering against wet ocean rock—then it’s a conclusion of a magnificent orange streak as the sun disappears here and reappears elsewhere in the world, giving way to a crescent moon, blue fading to black, families retreating to inland campsite for the evening, the crickets coming alive.

As I sit that night and watch the ocean swallow me alive, one feels insignificant and small.

June 2

Vince sets me off at the supermarket in Port Hedland, which is a massive mining town on a scale that I have never seen outside of Mt. Isa. “It’s a strange town,” one of the locals tells me while I’m playing my guitar. “ Possibly a temporary one, maybe we’ll be lucky if it lasts twenty years, destined to be a ghost town.”

He drops two Aussi dollars in my case. “But don’t tell anyone I told ya that mate,” he says, smiles and walks off.

I make it to the edge of town from a guy named Ian, who picks me up in a large commercial truck filled with crumbles of concrete. His job is to take the load to the local dumpsite.

“Why we bury the rubbish when we can recycle it, I don’t know,” he says. “All we’re doing is polluting our country.” Ian is an older-looking fellow, probably in his early sixties.

A lady at a small wooden booth checks us as we drive in. “I’m Ian from Gay Edwards Plumbing, delivering this fine load of rubbish to you,” he says with a flashy smile.

“My company has to pay seventy dollars a ton to drop rubbish off here,” he explains to me. “In Sydney, where I am from, it’s 360 dollars a ton!”

The scale weighs us and we are carrying 3.22 tons of concrete.

Ian has lived in Port Hedland for eight years and tells me he has grown to love the desolate areas. “There’s no kind of super highway like there is from Los Angeles to Las Vegas,” he says. “Here, there’s just a lonely road and the bush, mate.”

Ian is a self-proclaimed liberal. “Anybody that says guns can curb violence is talking rubbish. You can’t curb violence with more violence.”

He sets me off and I start walking until I’m given one short lift from a guy delivering some type of refrigeration unit. I walk until dark and no rides come so I walk off into the bush and make quickly make myself a fire. I heat up my canned beans for supper and read my book. There is the sound of wind and nothing else and if solitude had a sound, it might sound just like it does now; a distant whisper in the wind.

June 3

Grace comes to me in the morning after walking for a few hours as the heat begins to rise. I’ve got half a gallon of water left and it’s getting a bit depressing after the hundredth road train I count passes me by. Suddenly, a silver road train with three long trailers pulls over to the side of the road.

The hitchhiker relies on impulsive attempts at good deeds. I then meet Derek, who has been on the road for three days straight. “My truck broke down in Broome,” he tells me. “I had to wait on the side of the road for the mechanic. It took hours. “His recent experience of being stranded in the outback is related, although mine is partially by choice and his was not I suppose.